Poor Pogo has had a rough few weeks. Apparently he had been hit by a car in September. He was a stray, and they couldn’t find an owner. He had his left hind leg amputated on September 26th. A very kind family adopted Pogo from the Tacoma shelter on October 5th. Because Pogo was wearing a cone, due to the leg surgery and being neutered, the slip lead he had on when he left the shelter got loose on the ride home. When he arrived at his new home, the slip lead came off, Pogo got loose, and his new family discovered that he could run really fast on three legs. They had a few sightings of him over the next few days, including at a gravel pit 2 miles away. This was an active industrial site, and not a good place for a dog to be.

When Tino and I went to search for Pogo, after he had been on the run for 4 days, we picked up the scent item from Pogo’s new home, and started driving to the quarry where we would be accompanied by a supervisor, for safety. When I called the quarry to tell them I would be there in ten minutes to start the search, they said they actually had eyes on Pogo, who was stuck down in a deep pit. I told them I would be there in ten minutes, that I had years of experience catching frightened dogs, and that no one should approach him before I got there. Apparently my message didn’t reach everyone. They went in after him, and he scrambled out.

When I was about a block away from the quarry entrance, I saw Pogo running through traffic. It was a busy, winding road, with blind curves, no shoulders, steep drop-offs, and people speeding frequently. Some cars stopped to try to help Pogo and some cars tried to get around. He looked so sad, hobbling around the best he could, avoiding people. I wanted to tell people to not approach him, but I also had to get my car off the road somewhere on this narrow, winding road with no shoulders. Before I could intervene, Pogo ducked under a guard rail and headed down a very steep slope, through the brush. At least he was off the road. I could hear his cone crashing through the undergrowth.

I drove about 200 feet away to find a narrow place to park. When I got back to the place he had gone down the slope, I started down the hill, without my search dog, thinking that he was probably going to just be stuck in the bushes. It turned out that the brush thinned out towards the bottom of the slope, and it appeared that Pogo had found a deer trail to get him out to a large field that had been cleared as part of a restoration project for the flood plain of the Puyallup River. I went back to my car to get Tino, to follow the scent. By that time, Pogo’s new owner was able to come and join the search. He had bought a drone to search for Pogo. Since there was a large open field, I suggested that he fly the drone while Tino followed the scent.

The scent trail took us out to the restoration area, the size of several football fields, covered in green reseeding spray. It probably wasn’t going to harm Tino, but I didn’t have time to ask anyone what the formula of this reseeding spray was. I reasoned that, since it was for habitat restoration near a river, they probably wouldn’t use anything toxic, right? Tino followed the scent around in a loop, heading back towards the quarry. After we had been searching for about half an hour, Pogo’s owner said that he saw Pogo on his drone camera, and he was down by the river. He sent me the coordinates. By the time we got close, Pogo had moved quite a bit, and he sent me the new location.

Tino and I got onto the scent trail along the river, and eventually I could even see Pogo’s footprints in the mud as we tracked his scent. We came to a place where the ravine narrowed and the river curved left when it hit a cliff of sand. We could see Pogo ahead in the distance, maybe 100 yards up, somewhat trapped in a narrowing area between the river and the steep slope.

Just about that time, one of Pogo’s owners showed up at the same location, and I instructed her on calming signals. I gave her the can of Vienna sausage I had in my pocket, and a slip lead. The idea was for her to approach slowly and use calming signals to get Pogo. I couldn’t do the calming signals myself because I had Tino with me, and we didn’t know what Pogo might think of my 100 pound dog. Normally, I might just set a humane trap, but in this case, we would have had to carry the trap for half a mile, which wasn’t practical. As she was moving closer to Pogo, she was looking down at her footing, and she didn’t see that Pogo had seen her, and was starting to move away. I couldn’t really shout at her to stop approaching, because that would defeat the purpose. I texted her and called, but she couldn’t hear her phone because of the sound of the river. By the time she realized I was trying to contact her, it was too late. Pogo had started to climb the steep hill, and he went into a heavily wooded area on private property.

Tino and I found our way up to the top of the hill on an old trail, away from the area where Pogo went. I knocked on the doors of both homes, but no one answered. Using my phone, I was able to figure out who lived at these homes, and I called and left a voicemail for one of them. From the street, I could look down over the fence. There was an area where the ground was less steep, and an old wrecked car was still there, being swallowed by the vegetation. It was a section of woods between the two homes, which was private property, but not maintained by either household. It was a buffer between the properties. It seemed like a good place for Pogo to hide and rest.

We walked back to my car, and then I drove to the road above the two homes in the woods. One homeowner called me back, and he gave me permission to go into the woods on the steep slope where the wrecked cars were. Apparently this corner had been the scene of accidents in the past, a curve on a winding road where people would often speed. There were two cars just left on the slope, where no one bothered to haul them out because of the steep terrain. While Tino waited in the car, I made my way down the slope to quietly look for Pogo. One of his owners remained on the shore of the river, to watch for movement from below, and the other stayed up by the road, to be ready to intervene if Pogo ran out towards the deadly road.

I spent two hours traversing 350 feet so that I could be as quiet as possible. I used the noise of the cars on the road above to mask any sound I might make. The obnoxiously loud cars that kids drive turned out to be useful for once, allowing me to take several steps each time one roared by above us. I could see a small clearing in this hillside forest, with a pool of sunlight, and an area less steep, where a dog might rest without having to worry about sliding down the slope. One hour into my search, I caught a glimpse of what I suspected was Pogo’s cone catching the sunlight. I wanted to be very careful not to make him bolt because he was just above a cliff, and he might fall over the edge and into the river if I startled him and made him run downhill. If he ran uphill, he would probably end up on the dangerous road. I spent another hour getting closer without him knowing I was there, sometimes moving about a foot per minute, planning where to step, using the noise of the road to mask my progress.

When I finally got in the range where I could toss treats to Pogo, a new problem occurred to me. I hadn’t startled him yet, but would he be freaked out if he suddenly discovered that I was close to him? I didn’t know the best course of action. I felt that my next decision could literally be life or death for Pogo, and I did not feel confident that I was making the right choice. I always rely on my years of experience in these situations, but I had never been in quite this predicament, with a three-legged dog wearing a cone, on a steep slope between a cliff and a dangerous road. I texted Pogo’s owners that he was in sight, and I would be trying to get him to come to me soon, so they should be watching from above and below. I also posted in the UBS 1st responders group that it would be good to have volunteers on hand in case Pogo ran again.

As I sat there in the dirt, among the ferns, I had Kelsy with me. Of course, I always have Kelsy with me in my thoughts. Either I can actually picture her there with me, or if I am concentrating on something else, then she is just out of view, the way a dog might be, perhaps in the other room. In this case, I asked Kelsy to help me. I am not one to ask for any sort of divine intervention, even from my own secular saint. I asked Kelsy to go get Pogo and bring him to me, but of course she didn’t, and I wasn’t really expecting her to. It sure would have been cool if she had. As I sat there, for what seemed to be a very long time, a hummingbird came and talked to me. She lingered for several minutes, hovering in front of me, about 6 feet away. She spoke to me in her hummingbird language, saying things I could only guess at. I like to imagine that the hummingbird was Kelsy, coming to give me advice or words of encouragement, but that was just a pleasant thing to imagine. The very real hummingbird was nice to see, as I was trying to decide my approach.

In that moment, I thought it would be nice to have a Vienna sausage gun, some sort of air powered device that would silently propel bits of sausage to just the right place. I wanted to toss the sausage bits to where Pogo could get the scent, but I didn’t want to scare him. My best case scenario was that he would follow a trail of Vienna sausage to my location, then realize I was there, sitting calmly, no threat, with more treats for him. I could also imagine that one of my tosses would bounce off a hazelnut branch and hit him right on the cone, scaring him and making him run. I actually did a pretty good job of flinging globs of stinky sausage, but they didn’t seem to have any effect. Pogo did look around a bit, and sniff the air, but he didn’t get up and try to locate the sausage chunks. I began to wonder if he might be stuck, or in a mental fog because of his trauma and possibly from infection or illness.

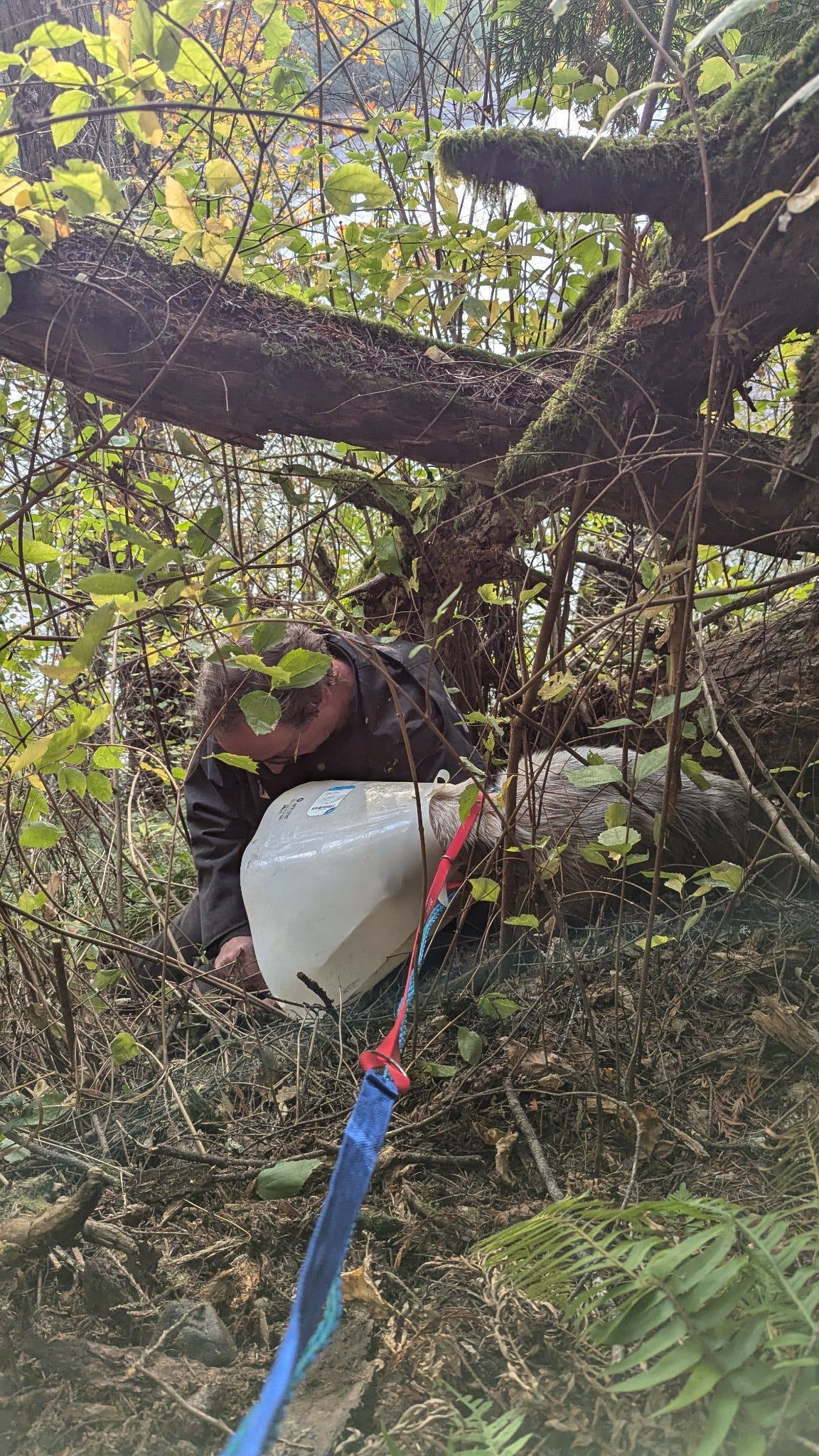

Because he wasn’t reacting, I slowly moved closer until I was about ten feet away. I tossed sausage bits that dropped right in front of him, right through his field of view. There was no way he couldn’t know that the sausage was there. What did he think? That sausage just rains from the sky sometimes? I moved closer. He didn’t turn to look at me, but I wonder if he caught a glimpse of me through his cone, or if he smelled that I was close. He slowly got up and moved away, almost crawling, down the slope about 20 feet, looking for a good escape route. He came up against a log that was too wide for him to get over easily, with the cone and missing a leg. He wedged himself in to the space below the log, and his cone caught on a branch. He was almost stuck. I moved within 4 feet, just by scooting along the ground as quietly as I could. Because of the steep slope, it was easy to slide down between the ferns. He looked over the log, thinking about trying to escape, but then he stayed put.

Slowly, I moved to within reach, so I could give him some sausage. He hesitated, but then he ate from my hand. He seemed to realize I was not going to chase him or try to grab him. I moved close enough to pet him, and he allowed it. I petted him under the chin, so he could easily bite me if he wanted to. It was my way of telling him that he was in control of the situation, and he could tell me to stop if he wanted to. He allowed petting, although he didn’t quite show that he enjoyed it. After maybe ten minutes, I could pet him all over, and I put the slip lead on him. I texted his owners that I had Pogo on a leash. It had taken me three and a half hours to slowly get close to Pogo and get a leash on him.

Although I was very relieved, the problem of what to do next was a major challenge. Also, my phone had died. I could still use my watch for phone calls and texting. I asked Pogo’s owner to come up from the river to the street, and then to make his way down past the wrecked cars to our location, quietly. I was able to tell him our precise location with an app on my watch. As we waited for him to climb all the way to the top of the hill and then back down, it was nice to just hang out with Pogo and build a bond. He had picked a nice spot, in terms of the view, even though it was a terrible location to try to extract him from. It was a warm afternoon. I could hear ravens in the distance. We looked out over the Puyallup River as the sun got low in the sky. The river was white with glacial flour, and the angle of the sun made it very bright. I posted to the UBS 1st responders group that I had a leash on Pogo. I speculated that we might need the help of WASART to get out.

I would have been happy to pick Pogo up and carry him up the hill. The only problem was that the steep slope would crumble under my feet with every step. The only way to get up the slope would be by hanging onto hazelnut branches and ferns as I climbed, and I couldn’t do that and carry Pogo. Although he was warming up to me, I still felt like he might bolt if I slipped and dropped his leash, or if he was spooked by something falling. We couldn’t risk that happening.

As we waited for his owner, I eased Pogo out of the spot where he was semi wedged under the log, and pulled him closer to me, gently. He didn’t resist, and he seemed to like just hanging out with me. He no longer looked around for an escape route. He was like, Oh, good, you’ve come to live with me in my new home in the forest. By the time his owner got to me, with more leashes, I had actually spent more time with Pogo than his owner had been able to, before the escape. I had the owner approach slowly and quietly, to keep Pogo comfortable. We got a second slip lead on him, and we tried to start getting him up the hill. It didn’t go well. He didn’t want to go. I could lift him and set him up higher on the hill, and then get my self up to the new level, but that was slow going, and it made him nervous. We only made it about 20 feet up the hill, and I decided to go ahead and call for WASART.

Washington State Animal Rescue Team is a volunteer organization that helps recover animals from wilderness areas when it would be hard to get them out any other way. They have equipment and training to, for example, get a 1700 pound horse out of a ravine he has fallen into. It seemed like overkill to have a whole team of volunteers and equipment come and help us with Pogo, but I just didn’t think we were going to be able to get him out safely on our own. I texted our volunteers, Dori and Diane, that I wanted WASART to come help us if possible.

The first WASART volunteer to arrive on scene was Joy, who had come from Enumclaw. I talked to her through my watch, and explained the situation. Pogo’s owner was able to take a picture of how we were situated, so she could formulate a plan for extraction. She took a bit longer to get down the slope because she was setting ropes for getting back up. By the time she reached us, it was getting dark. I used the flashlight from my pocket to help guide her to us. Joy was very kind and knowledgeable, and skilled in her work. Also, she listened to me when I advised her on how to approach Pogo, which was pretty much what she had planned to do anyway. She asked me to let her know when she should stop, if Pogo was getting uncomfortable. Joy had a headlamp on, with the light shining out and her face in shadow, so I had no idea what she looked like, just that she was very kind and helpful. Later, when Pogo was safe at the top of the hill, I saw that there were at least three female volunteers in the crew, and I had no idea which one was Joy. She was just a friendly voice in the darkness.

The plan was to pull Pogo up the hill in a litter, which is basically a hard shell, I’m guessing made of fiberglass or plastic, which has a metal frame and a railing to attach ropes. The rest of Joy’s crew worked from above as she talked to them through her phone. They were going to drop the litter down from directly above our position. They occasionally asked Joy questions, but mostly we just waited. As we waited, Joy came closer to Pogo, to get acquainted with him and put him at ease. Pogo was kind of oozing down the hill, so I went around below him and pushed him up above a large Douglas fir tree. Then I wedged myself in between him and the tree, so he could rest his body against me. Joy offered us a bottle of water. I still had the empty can from the Vienna sausage, so I used that to pour the water into for Pogo. He drank the entire liter of water, except for what he spilled on me.

As we waited, Pogo completely melted into my chest. It reminded me of when Raphael finally accepted me, during his long rescue effort, and draped himself over me to claim me as his human. I rubbed Pogo’s chest with my free hand, and if I ever stopped petting him, he nudged my hand to keep petting. I felt so good that Pogo accepted me and liked me. It seems like all I ever want in life is for the dogs to like me. As I was lying in the dark, on a steep slope, with a tree keeping me from falling down, with a dog in my chest, I thought that this was the pinnacle of success for me, saving Pogo. I imagined if I could go back and talk to myself in high school, and tell that version of me what my life was like, that I was lying in the dirt with a stray dog in the dark and I was the happiest I could possibly be, what would my high school self think of that. I didn’t even like dogs when I was in high school.

After about half an hour of Joy easing closer, she started to pet Pogo, and he accepted her. When Zach finally rappelled down to us with the litter and supplies, he brought a harness and a muzzle for Pogo. The muzzle was standard procedure because dogs in this situation can get nervous about being strapped to a litter and hauled up a hill. Once Joy got the muzzle on Pogo, which went pretty easily, I took his cone off, just to make him easier to manage. He looked like a real dog again, without his cone. I got him into the harness, which was sturdy and deluxe, designed to hoist a dog into a helicopter. It fit him just right. I tried to get all of the straps hooked up right, but I’m not sure if I did. Joy and Zack verified that the harness was secured properly. Once he was in the harness, we all started getting him into the litter, which was a challenge because of the slope.

Pogo was a good sport about it and didn’t resist much. He seemed to understand that we were all there to help. Once placed into the litter, with padding stuffed under him, Zach ran straps over him, and through the harness, securely fastening him to the litter. Joy and Zach ran through their checklist to be certain everything was secure. My phone had died, so I asked Pogo’s owner to snap a picture of Pogo secured in the litter. I think it was about 8:30 by the time we were ready for extraction, more than 11 hours after the start of the search.

Zach radioed up to the top to start pulling, and they began to move the litter up the hill. I was nervous about this, wondering how Pogo would do. I couldn’t see Pogo because Zach was between us. After about 20 feet, Zach radioed up to stop pulling because Pogo was struggling to get out of the litter. He was trying to get back to me. I scrambled up the slope, holding onto branches, so I could be next to Pogo. As long as I was in sight, and I could pet him now and then, Pogo relaxed in the litter. As they hoisted him up about 300 or 400 feet of slope, I scrambled up beside the litter, staying near Pogo and keeping him calm. Once they finally got him up to level ground, they hoisted him over the chain link fence, lifting him over their heads. I climbed over the fence using the ladder they provided, so I could be close when they unstrapped Pogo from the litter and put him in a kennel. I wanted to be sure there was no chance for him to bolt, again. Once he was safely inside his owner’s truck, I could finally relax.

It was 9 o’clock, and I had been finding Pogo for 12 hours. I was exhausted. I went to the car where Tino was sleeping, and he was relaxed. He didn’t even need to pee when I took him out on a leash. Tino went to visit the WASART volunteers, who were loading up their trailer full of equipment. I thanked them all for helping us. Then Tino and I hurried home to get Raven out for a walk. The dogs didn’t seem upset at all that we had been gone for longer than usual. It was good to be home with my family, knowing Pogo was safe.

I write these newsletter articles in hopes that people will find them interesting. People are often curious about what I do, so I try to give them a window into my world. I also write these stories so I can educate people about what to do and what not to do, to help lost dogs and cats. I also like to write about my adventures with my dogs because of Kelsy. Of course, pretty much everything I do these days, with Three Retrievers Lost Pet Rescue and Useless Bay Sanctuary, is all because of Kelsy, because we accidentally happened to see a flier on the bulletin board at the off-leash park offering training on how to use dogs to search for lost pets. I built my entire life around Kelsy and our work, and when she died, I realized that she meant more to me than I ever knew. Since Kelsy died, more than 8 years ago, I have thought about her every single day. One of the ways Kelsy has had the greatest impact on me is that, once she was gone, I wished I had more pictures of her, and more of a detailed record of her life and work. Because of Kelsy, I make a point of capturing details of the searches I do with my dogs. Because of Kelsy, I now have almost 200,000 pictures on my phone, mostly of dogs. Who we are, as individuals, is determined by what we pay attention to, and what we remember. Although what I do is uncommon, it is exactly what I want to be doing. I am happy with this life that was built around Kelsy, and still revolves around her, what she taught us, and what she represents.

In this newsletter, I have written more than 250 articles about our adventures, and about better ways to help dogs and cats in need. I hope that people have enjoyed these articles and learned from them. Even if no one read these articles, I would still write them because I like to have a record of this life that Kelsy and I built. My dogs are my family. When I work with a search dog, we are something more than what we would each be alone. I especially like that we work in the service of animals. Animals working for animals. I always want to remember days when I work with Tino on a search. I always want to remember when we are able to help dogs like Pogo. As I was lying there in the dark, on the slope, holding Pogo to my chest, waiting for extraction, it was easy to imagine that Kelsy, the black Lab, was right beside us in the dark. In that moment, which I always want to remember, I was the happiest I could possibly be, in this life that Kelsy and I built.

Such a meaningful way to remember Kelsy and to honour her, in the service of animals in need.

Wonderful. No words. Thank you James.