Read this before you hire a search dog for your lost cat.

I will not bring out a search dog to look for your lost cat until you have read this and understand it.

When your cat is missing, you don’t want to read a long article. You just want someone to come and find your cat. I understand that. I have lost cats in the past, and that’s why I do this work, because I have been in your situation. However, if you don’t understand how search dogs find cats, you are probably going to have unrealistic expectations of what a search dog can do. In almost every case, the owner of a lost cat insists they want my scent trailing dog, Tino, to search for their lost cat even though my cat-detection dog, Raphael, is the one who has the best chance of finding your cat. When I don’t want to use Tino for a search, it’s not because I want to deprive your cat of the best chance of being found. It’s exactly the opposite. I want to give your cat the greatest opportunity of coming home, and that is with Raphael, the cat-detection dog, in most cases. I absolutely love Tino, more than words can express, and he is an excellent search dog for certain types of searches. If I thought he was your cat’s best chance of coming home, I would absolutely use him. People seem to be offended or disappointed when I don’t use the scent-trailing dog to search for a lost cat. Based on my 17 years of finding lost pets, I’m going to use the search dogs that will have the best skills for your cat’s situation. Usually, that is Raphael, the cat-detection dog.

When people hear of a dog that finds lost cats, many people think the search dog is going to follow a scent trail to the hiding place where their cat has been ensconced, and they will know for sure where their cat is. Unfortunately, that is not how dogs find lost cats (in most cases), and it is important that you know why, before you hire a search dog to look for your missing cat.

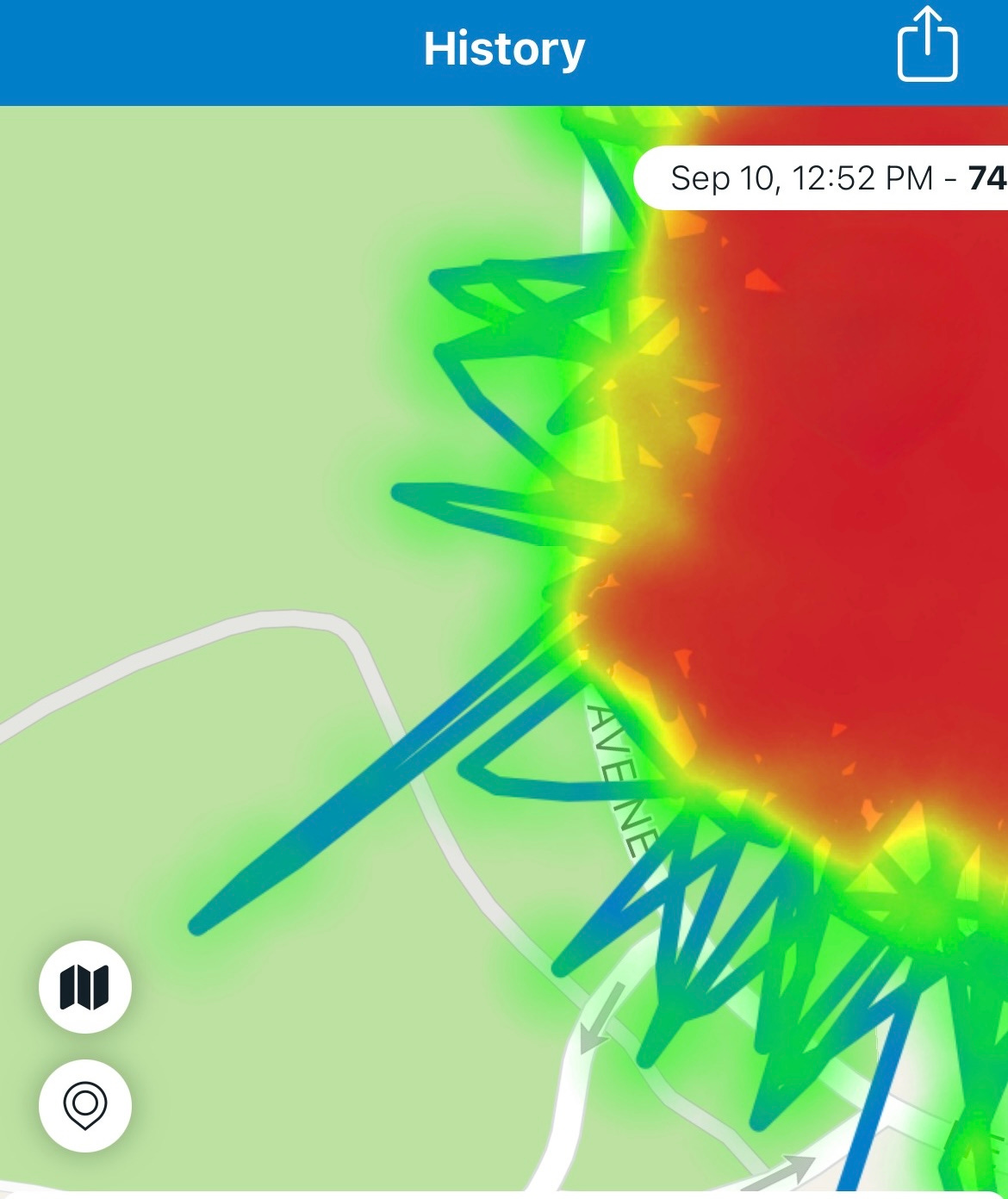

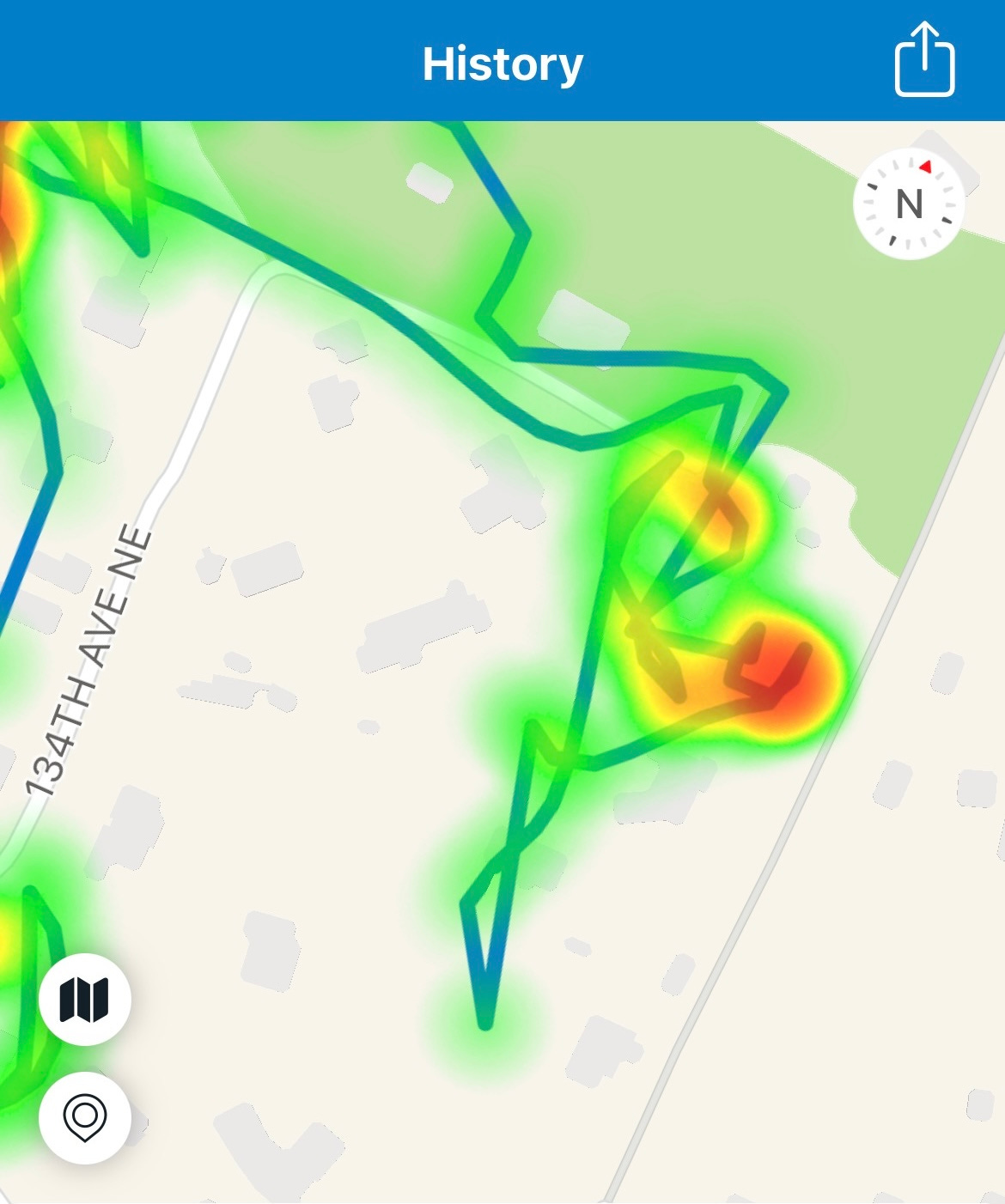

Search dogs can and do follow the scent trails of missing dogs as they run in fear or go off exploring. Dogs tend to run many blocks or many miles when they disappear, and they leave a scent trail from point A to point B. Cats behave differently when they roam or flee. Even the most adventurous cat will usually stick to known paths and familiar territory. Mostly, cats move a little way, stop and leave a scent pool, move a little farther, and make another overlapping scent pool. What you are left with is not a scent trail from point A to point B, but a series of directionless pools of scent. Because individual cat trails are difficult or impossible to follow, we teach our cat detection dogs to find any cat they can. They are methodically searching areas of high probability, under our direction, looking for any cat they can find. The cat detection dog will become alert and excited when entering a pool of cat scent, and he will become excited and whine when he approaches the position of a hidden cat. If he finds a cat other than the one we are seeking, we tell him, “Good boy, go find another,” and give him a treat reward. Below are two pictures showing the history of a cat with a GPS tracking collar over a long period of time and a shorter period. As you can see in this graphic illustration, cats don’t usually leave scent trails from point A to point B. They usually leave a web of overlapping trails, or large directionless pools of scent.

Although the cat detection dog almost always finds some cats on a typical search, there’s about a 25% chance for the dog to directly find the cat we are seeking during the typical three-hour search. Most of the time, we leave the owner’s neighborhood without pinpointing the location of the cat we are looking for. This doesn’t mean the cat wasn’t there, necessarily, because we may have dislodged the cat from his hiding place when the search dog approached. It is never our intention to cause a cat to move out of her hiding place, and we approach the search in order to avoid making a cat run. Usually, we will do the search in a pattern such that, if the cat does move out of hiding, she will move closer to home. In about a quarter of our cases, the cat was found shortly after we searched, and this may be because the missing cat came out of hiding when the dog approached. (All our cat-detection dogs are friendly with cats, but the cat doesn’t know that.) Only in about 25% of our searches does the search dog find the hidden cat directly, or remains of a deceased cat.

In most cases, I would recommend that cat-detection dog as the best type of search dog to look for a cat. In some cases, for example, when an indoor only cat has escaped outdoors in the past day or two, it may be useful to use the scent-trailing dog first, to establish a direction of travel. We have used this method successfully on about fifteen occasions so far. The scent trailing dog directed us to a new area to concentrate our search, and then the cat-detection dog pinpointed the location of the cat. The scent trailing dog is usually not great at pinpointing a cat because the scent trail gets all tangled up and the direction of travel is no longer apparent. If your cat is indoor only and has just recently escaped, it may be best to use this two-dog approach.

Why would you want to hire a search dog if the odds of immediate success are only about 25%? There are several reasons, and you should consider these factors when deciding whether a search dog is worth the time and expense.

· Value of a thorough search on neighboring properties.

· Attract attention to the search.

· Know where cat is not.

· Find evidence of predation.

· The dog search is not a substitute for everything else that needs to be done.

· Other tools used during the search.

· The value of experience with many searches.

When your cat is missing, you suddenly get to know neighbors that you have lived near for years but you’ve never really talked to them. I know this from my personal experience of losing a cat. You want to search your neighbor’s property very thoroughly, but it feels awkward to say, “I wasn’t all that interested in talking to you for the last eleven years, but now I want to snoop around your tool shed.” Also, your neighbor may say he has checked his garage and your cat is not there when in fact your cat may be well hidden inside the garage. When you hire a cat-detection dog to do a thorough search, we are a disinterested third party. It feels less awkward for the cat owner and the property owner when a professional with a trained dog comes to do a thorough search. This way, it doesn’t feel like you are poking your nose in your neighbor’s business. We are just looking in those hiding places of highest probability. Also, the junk in one person’s back yard looks much the same as the junk in another person’s back yard, and we aren’t making any judgments about the property owner. We are just looking for the lost cat. Having this search done by professionals makes it easier for everyone.

Another value of the search dog team is that it draws attention to the case of your missing cat. At least once a month, there is a new flier for a lost pet on the telephone poles in my neighborhood. I stop to look because that is my area of interest, but most people just cruise on by these fliers without paying much attention. Hopefully, if your cat is missing, you have bombarded your neighborhood with fliers and signs so that no one within a three-block radius could possibly be unaware of your missing cat. Even if you have done a good job with posters and fliers, the presence of a search dog team raises the level of awareness. It involves people in the search, gets them excited and motivated, and elicits useful information even when people have seen the posters and fliers. In many cases, the search dog team will get a critical tip from a neighbor. We feel like asking, “Well, why didn’t you come forward with this information when you first saw the missing cat flier?” For whatever reason, the search dog gets people talking and draws out more and better tips. Some of these leads are mistaken or not actionable, but it provides more information that the cat owner can act on.

If the search dog leaves after three or four hours of looking, and your cat has not been found around the twenty or thirty homes closest to your house, you will at least know that your cat is not in that zone of highest probability. It is possible he moved out of his hiding place as the search dog moved through, but you know he is not hiding under the Wilson’s shed or in the Johnson’s garage. This not only allows you to stop worrying about those possibilities, it lets you focus your search on the next most likely scenarios. Cats do occasionally hitch a ride out of their neighborhood in a moving van or get locked inside a vacant house for sale. These are not as likely as simply hiding under the neighbor’s shed, but such scenarios become more likely when you rule out the most likely situations. An effective search for a cat involves ruling out all the places your cat is not. You need to verify that your cat is not at the local shelter, not at the local vet, not just hiding under the bed, and not in the rafters of the neighbor’s barn. You can rule out most of those places yourself. You can even do a thorough search of your neighbor’s property without a search dog. It’s just a lot easier and more effective if you bring in the search dog.

Another advantage of the search dog is that her nose can point out signs of predation that a human would overlook. This has happened in over 125 cases. The possibility that your cat was taken by a coyote or another predator is one of the least likely things that could have happened. We keep records of the searches we perform, and their outcomes. We don’t always know the final outcome, so our statistics are incomplete. However, we can come up with a minimum and maximum probability of death by predator, accounting for the missing data, and so far the number of pets lost to coyotes and other predators is between 3% and 10%. Almost every other possibility—being at the shelter, hiding under a shed, being stuck inside the wall, hopping in a moving van—is more likely than being taken by a predator. Still, it does happen from time to time, and the search dog has found physical evidence where humans have passed many times without noticing. In four recent cases where we know a coyote took the pet, evidence of a kill was found within a hundred yards of the pet’s house. If we do a thorough search of the areas of highest probability in your neighborhood and the search dog does not find any evidence of predation, then you can say that the likelihood is even lower than the average of 3% to 10%. You can concentrate on other possibilities and spend less time thinking your cat has been killed by a coyote. It is also important to note that in almost all of the cases where my search dogs found evidence of a predator attack, there was little or no chance that I could have located that evidence just looking visually, without a search dog. In almost every case of a predator attack on a cat, it was the search dog’s nose that located the evidence.

A search dog is just one tool, and not a substitute for all the other ways of finding a lost cat. It wouldn’t make sense to look for your cat by only searching houses with odd numbers and not the even-numbered houses. Neither would it make sense to only hire a search dog if you don’t plan on checking the shelters, posting the fliers, visiting the vet, and all those other useful techniques. The use of a search dog is most likely to be helpful when used in conjunction with all other avenues of discovery. Likewise, a visit to the shelter won’t find your cat if he’s still hiding in a tree in the neighbor’s back yard. Your goal in your search for your cat is to check the most likely places first, and then do a thorough search of every place your cat could be. The search dog team covers those aspects of the search that an unaided human could not do as easily or as well.

Because the search dog is just one tool, the handler may bring other equipment on the search. We can bring listening devices to hear faint sounds in crawlspaces and in hedgerows. We have fiber optic scopes to look in crevices and around corners. We will have high-powered flashlights to detect eye reflection in crawlspaces. If predation is suspected, we have forensic chemical tests to help determine if the evidence is relevant to your case. Most of all, the Missing Animal Response Technician handling the dog and guiding the search has the experience of hundreds of other searches, plus training specific to this situation. You should not be an expert in finding lost cats because, hopefully, it doesn’t happen to you very often. You don’t learn brain surgery just in case someone in your family might have a tumor someday, and most people aren’t experienced with plumbing repairs because it is simpler and more effective—and often cheaper—to have a professional handle situations that come up rarely or never. We know what works and what doesn’t when you are searching for a lost cat. Many web sites have free advice that is generally useful in finding a missing cat, but the handler that comes with the search dog can usually answer questions specific to your case because he has experienced the same situation with someone else’s lost cat. Many of the techniques commonly employed by inexperienced people to find a lost cat are unhelpful, and some do more harm than good. We can guide you to the most effective methods and steer you away from ways that have failed in the past.

When you should probably not hire a search dog:

· If you can’t get permission to search a majority of private property in the area of highest probability.

· If you aren’t willing to take all the other steps necessary beyond the search with the dog.

· If your cat has been missing for more than several weeks and there have been no reported sightings.

· If you haven’t already done a thorough search inside your house, including places your cat wouldn’t normally go.

· If you don’t have a reasonable understanding of what a search dog can and cannot do.

Toward that last point, this information is provided so that you don’t have unrealistic expectations of the search dog, and so that you get the most out of your time and money, with the highest chances of success. Every case is different, so be sure to ask questions of the search dog handler before he comes out to work the dog.

You should also understand the physical limits of the search dog. He can only smell what he can smell. The abilities of a dog’s nose are amazing, and a thousand times more powerful than the human nose. However, if the wind is blowing the wrong way, or if the conditions are too hot and dry, a search dog can walk right by a hidden cat without knowing it. We try to minimize the risk of this failure by searching in the best weather conditions (cool and moist) and accounting for wind direction. Still, in many cases, I have had a proven search dog walk along oblivious to a cat that we humans can plainly see fifteen feet away. This is not a failure on the part of the search dog. First of all, he is supposed to be using his nose, not his eyes. Second, dogs can’t really identify objects that aren’t moving: if I throw my dog’s favorite orange ball onto a green lawn while he is not looking, that ball, which a human can see from fifty feet away, is almost invisible to his eyes and he must use his nose to find it. If the ball is moving, he can spot it from a mile away. Cats instinctively know that they become invisible to dogs if they hold still. It is the job of the search dog handler to work the search pattern with the wind flow to give the dog a chance to smell those cats, seen and unseen. Also, dogs can’t climb trees or jump into the rafters of a garage, so the search dog may indicate the presence of a cat without being able to pinpoint the location of the cat. Dogs also lose interest in a game after a certain amount of time, so we usually limit the search to three or four hours, depending on the weather conditions and how the dog is holding up. I can’t push a dog to search. He has to do it because he enjoys the game. The search dog is an amazing tool, but he has his limits, and the person relying on the search dog needs to be aware of those limitations.

Knowing everything I know about search dogs, I would certainly want the services of one if my cat were missing. When my cat did go missing in 1997, I wish I had been able to use the services of a professional with a cat detection dog. As helpful as we can be at times, we work best when the owner of the missing pet has a clear understanding of what we can and cannot do. I hope that we can help you. If you have any questions about how the search dogs work, or which dog we would use for your situation, please ask before the search dog comes out.

One additional note: it has been my practice to bring two dogs out when we search for a cat. In almost every case, Raphael will do all or most of the searching, and Tino will wait in the car. Social media has conditioned many people to think that dogs can never be left in a car unattended. I am not leaving Tino in the car because I am stupid or uncaring or lazy or uninformed. He is there, on standby, in case he is needed. I take measures to make sure he is not too hot. We can’t even search for a cat when the temperatures are too high, anyway. If you want us to come and look for your cat, it is very likely that one dog will be in the car while the other dog works. If you absolutely believe that a dog can never be left alone in the car for any length of time, then please don’t request the search dog for your cat. I love my dogs more than life itself, and I would never leave them in the car alone if I felt they were at risk.

If you haven’t already, please read the entire Guide to Finding Your Lost Cat.

James, thank you for sharing this information. Very interesting and educational. Thanks for your good works with your dogs.